The next time you are in a 60-foot-tall building, look down, says Dean Moel.

Then, he says, imagine being surrounded by water, and having to jump.

Moel was a the cook – and a trainer on a twin 40 mm anti-aircraft gun – on the only U.S. aircraft carrier sunk by enemy fire during World War II: The Gambier Bay.

As he stood between the concrete walls of the World War II Memorial on Sept. 14, Moel still had a hard time believing he survived the attack by Japanese ships, the sinking of his boat, and 45 hours of floating in the shark-infested waters of the Pacific Ocean.

The Gambier Bay, a small aircraft carrier, was one of several U.S. vessels attacked by one of the largest Japanese fleets of the war during the Battle of Samar in the Philippines on Oct. 25, 1944. The ship was damaged when an 8-inch shell exploded in the water near her, causing massive flooding killing one engine.

Crippled, the ship was unable to flee, making her an easy target for other Japanese vessels. She was hit by countless more rounds in a four-hour battle. She sunk at around 9 a.m.

Hundreds of sailors abandoned ship.

“It was listing to port, and I was about 60 feet from the water,” said Moel. “I jumped feet first.”

While some sailors found rafts, many others, including Moel, floated with only their life vests keeping them from sinking into the ocean.

Moel and another then-18-year-old Iowan, Henry McGlaughlin from Des Moines, got separated from the other sailors.

Soon, recalls Moel, McGlaughlin – hallucinating after swallowing too much salt water—swam away, saying he saw Japanese troops in the water.

“I tried to stop him, but I couldn’t,” recalls Moel. “I guess I was the last person to see him alive. He left me all by myself."

Staying awake, staying alive

Later that first night, Moel found a group of about 90 other sailors, all floating only in their life jackets.

He credits one of those sailors, Dick Pinch, with saving his life.

“I was about to fall asleep because I was so tired from all the swimming. He kept me awake by running his finger up my neck,” recalls Moel.

Forced to flee, the other ships in the U.S. fleet were not able to return to rescue the sailors for nearly two days.

After the first night, Moel says, he was able to stay awake, as the sailors helped each other hold on until the rescuers could come.

Some were killed by sharks. At least one sailor was attacked by a shark and lost both legs, but survived.

“I still don’t know why the sharks didn’t get me,” said Moel, of Lisbon.

Moel recalled his two-day ordeal while standing at the WWII memorial as part of the Sept. 14 Eastern Iowa Honor Flight. He said that after two days, when the U.S. could finally get ships to the area, his life jacket had rubbed so much skin from his neck that it was “all meat.”

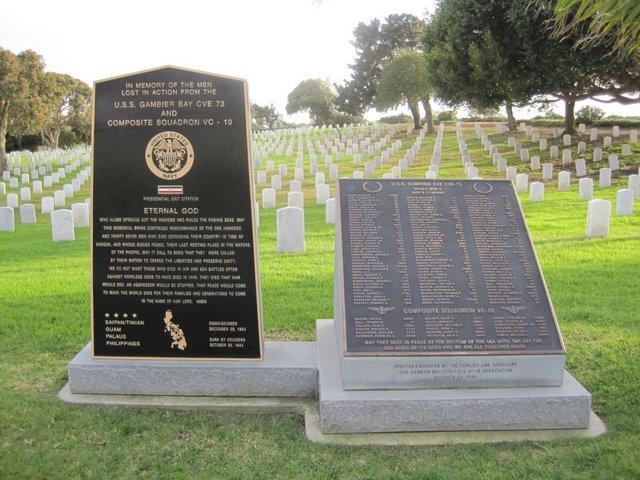

More than 100 sailors from the Gambier Bay and other ships in that battle died that day. They are memorialized on a stone near San Diego.

But despite the horror of having their ship attacked and sunk, the sailors were able to keep their humor.

As they watched the Japanese ships sailing away, one sailor – according to those who survived that day – looked at an enemy ship and said, “Hey, the son-of-a-gun is getting away.”

Presidential Citation

Although their ship was sunk, the sailors of the Gambier Bay and their fleet were able to stop a major and deadly Japanese advance.

There were 100 more ships in the water in the Leyte Gulf, and 115,000 sailors who could have died if the Gambier Bay had not helped repel the Japanese attack, said Moel.

“We got the Presidential Unit Citation for that,” he said.

After returning to the U.S., Moel and his shipmates enjoyed a 30-day survivor’s leave. He then was assigned to a sea plane tender.

“I was in Okinawa when war ended,” he recalled.

That was when being a cook brought Moel a unique reward.

A flight crew that he had fed well invited him to fly with him to Tokyo, where he toured bombing sites and the Emperor’s Palace. They returned to the ship a day before the peace treaty was signed.

The 12th year

Moel had quit school to join the Navy during the war.

“It always irked me when we were asked to fill out our forms, that I had to write ‘11’ instead of a '12’ for my education,” Moel recalled.

So, he went back to school, and earned his high school diploma. He spent most of his career in the construction and concrete business.

“I built the first grade school for Linn Mar when it was the only building in the area,” he recalls.

Moel has been retired for 22 years, and is a neighbor the son of another Sept. 14 Honor Flight participant, Irvin Clark. Clark was a crewman on an LST that was sunk after a kamikaze attack, and also spent some time in the water, waiting to be rescued.

Reluctant to go, but thankful that he did

Moel said he tried to get out of going to Washington, D.C.

“I never really did go for that stuff,” he said.

But now, he is very thankful that he did go.

“That World War II monument they built there is going be standing there forever – it’s that well-built,” said Moel. “A neighbor explained it to me before I went, but I could still not imagine what it is like. The memorial itself its fantastic the way they honor everything in World War II."

In addition to the WWII Memorial, Moel said what he remembers most about the day is the welcome the veterans received, both at Washington, D.C., and later that night when they returned to Cedar Rapids, where hundreds were waiting and cheering at the Eastern Iowa Airport.

“A lot of old guys had tear in their eyes,” he said. “That was really something.”

Comments

Submit a CommentPlease refresh the page to leave Comment.

Still seeing this message? Press Ctrl + F5 to do a "Hard Refresh".