John Gualtier still remembers, more than 66 years after the end of World War II, the first American soldier he tried to help on his first day as an Army medic in Europe.

“He was lying on his back, and didn’t look injured,” Gualtier told the students of Kelly Steffen’s history class on Friday.

But when Gualtier put his hand under the soldier to lift him up, he suddenly realized how that soldier had died.

“My hand went into the back of his head,” he told the class. “There was a large hole in his skull.”

For more than a year, Gualtier saw and treated countless war wounds. He turned 19 while his unit liberated a concentration camp. He saw countless head and abdomen wounds, as well as men who had lost both of their legs from the waist down.

“I’ve had men die in my arms,” he told the class.

Gualtier entered the Army as a truck driver; he said he still does not know how he ended up as a medic, or which commanding officer assigned him to that duty.

He told the students about how his experience impacted his life for decades after the war.

When he was 19 – “when I should have been home, playing football,” he told the class – Gualtier was assigned to enter a mass grave in a concentration camp, and find the living who had been buried alive.

Later, when a psychologist asked Gualtier how many dead bodies he had seen at one time, the former medic replied, “Three thousand.”

“He called me a liar,” Gualtier told the class.

But the photos in the book chronicling the history of his Army unit verify that he did indeed see thousands of bodies in that concentration camp. He also helped liberate American and Russian POWs at the end of World War II.

Army medics also treated enemy wounded, Gualtier said.

“After we treated all of our guys, we had to treat the Germans,” he said.

One student asked how treating enemy soldiers made him feel. Gualtier replied that he didn’t mind treating the Germans, saying they had been drafted to fight and did not really want to be there. He said the Germans who surrendered to his unit included young boys as well as 40-something men who had been taken from their beds in the middle of the night and ordered to the front lines.

But Gualtier also told the class that he had a brother-in-law who was beheaded in a POW camp in the Pacific. It’s harder, he said, to forgive something like that.

Gualtier candidly told the class about the psychological impact his war experiences had on him.

Three days after he returned home, his behavior was so drastic that his parents called the Army. That began decades of therapy, treatment, and depression. Gualtier, now 86, said he tried to commit suicide two times, and has always found it very difficult to keep a job.

“I still live that nightmare every day,” he told the class.

Because of his multiple experiences during World War II, the U.S. military asked Gualtier to volunteer for a study on PTSD, so medical professionals could learn more about how to help soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan who are also experiencing those effects of war.

For 14 months, Gualtier spent many days, in long sessions, sitting in a dark room, sharing what he remembered from his time as a medic. Finally, after 14 months, he told them he had had enough.

Several weeks ago, Gualtier, accompanied by VFW Post 8884 Commander Dale Henry, attended a session where the doctors who had spent those months evaluating Gualtier gave him a presentation detailing all of the things they had learned just from their conversations with him.

In addition to the memories of the wounded and dying that he tried to help, Gualtier said he still struggles with guilt, wondering if he did enough – if he did the right thing – for the men he tried to help.

He remembers the several times that he passed out. He remembers the horrible smell when his unit was a mile from a concentration camp.

Gualtier has since spoken to some soldiers after their return from the Middle East.

He has also spoken to many high school students.

That experience, he said, has been a life-changer.

Telling the class that Mrs. Steffen is “the young lady who turned my life around,” Gualtier told the students that while he still has those memories and nightmares, life is much better for him now.

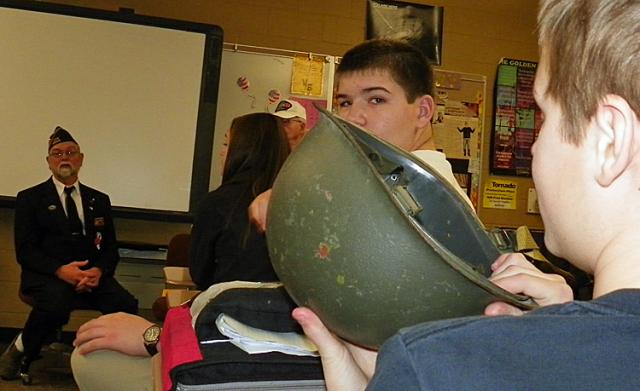

The heavy helmet that Gualtier wore during World War II is among the items on display in Mrs. Steffen's classroom, along with a 2008 article about him.

Gualtier spoke about how talking about his experiences has helped him to recover. He also told the class how his first wife, Marion (now deceased), an army nurse who once treated him, helped his recovery.

“She knew me when I was goofy,” Gualtier told the class.

Gualtier told the students that as a medic, he did not carry a weapon. He told them to never ask a veteran how many people they killed in war.

“They do not know, and it’s something they do not want to talk about,” he told the students.

Gualtier, who will go to Washington, D.C., this summer as a nominee for the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Volunteer Award, has spoken to hundreds of high school students at Vinton-Shellsburg and North Linn. He has also accompanied students on tours of VA hospital facilities, and has spent almost 7,000 hours as a volunteer, driving veterans to medical appointments at VA facilities and helping former soldiers to receive the benefits they deserve.

Gualtier told the class about how, around 1968, while he was being treated, someone told him he would qualify for government help because of the impact of the war on his health.

“So I filled out a bunch of papers, and soon I received a check,” he told the class.

He received $11.

“They thought my wounds were worth that much,” he said.

Gualtier was once wounded in the arm, and for that has been nominated for the Purple Heart. But he said that medics often did not receive recognition for injuries. “You just had to patch yourself up and go on,” he said.

Gualtier and VFW Post 8884 Commander Dale Henry presented Mrs. Steffen a certificate from the National VFW, thanking her for what she does to support veterans.

Click HERE to see a video of John Gualtier speaking to another class at VSHS last Friday.

Comments

Submit a CommentPlease refresh the page to leave Comment.

Still seeing this message? Press Ctrl + F5 to do a "Hard Refresh".